Moçambique's Inhambane province is beautiful:

coconut palms, white beaches,

blue sea, rolling hills, fresh fruit everywhere,

dhows floating gently in the sun:

exactly what you imagine a tropical paradise to be.

It's Good Water

August 10 - 13 2005

Moçambique's Inhambane province is beautiful:

coconut palms, white beaches,

blue sea, rolling hills, fresh fruit everywhere,

dhows floating gently in the sun:

exactly what you imagine a tropical paradise to be.

Now imagine you have been living in a rural Moçambican community all your life. Imagine that every day you have to walk fifteen kilometres for your basic water need. Imagine that you never wash your clothes because water is not available. Imagine that every time you take a drink of water you risk contracting a fatal illness. Imagine that you have never bathed your child because it's more important to put the water on your meagre food crop. Imagine that you have no time to learn to read or write because the search for water takes all your days. Imagine your children and your childrens' children repeating this for every generation.

Now imagine a clean clear flow, in the centre of your community, available every day, every hour. Imagine you can stay home with your family because you don't have to rise before dawn to walk to the river. Imagine you could achieve this for less than 50 cents. Imagine your life changing.

This is the promise of the PDÁRI project in Moçambique's Inhambane

province. At the beginning of August 2005, I visited four sites of the pilot

project, in the Homoine district, which aims to provide clean water to rural communities, within a

framework of community ownership.

We hear a lot about "meeting

requirements", "ownership", "consensus", "reliability", and "sustainability".

It's humbling to see what those terms mean in the context of a poor rural

community, where the  average income is less than $1 a day, when average life

expectancy is 40 years (and declining) and where average infant mortality

is 158 per 1000 (for comparison Canada has an average income of $80.76/day,

a life expectancy of 80 (and rising), and an infant mortality of 5.3/1000)

average income is less than $1 a day, when average life

expectancy is 40 years (and declining) and where average infant mortality

is 158 per 1000 (for comparison Canada has an average income of $80.76/day,

a life expectancy of 80 (and rising), and an infant mortality of 5.3/1000)

"It's good water" - an everyday phrase that we take completely for granted. We often say something is "good" when all we mean is simple passive acceptance, something pleasing or pleasant but not unusual, a normal part of everyday life. But when spoken by a chitswa woman, explaining that, for the first time, she has been able to keep her child clean and disease free, you come to a realization of exactly the multiple meanings of "good".

Roget's thesaurus lists 432 entries for Good including : acceptable, agreeable, exceptional, precious, satisfying, wonderful, worthy

Acceptable - community acceptance is an essential part of defining the standard

for the water. Imagine if your water

had a salinity of 2000mg/l. That's 500 times higher than the strictest Canadian

standard. So do you deny the community this water? It's not up to you. The

community accepts this water. It's good water, because it's here, now.

Imagine if your water

had a salinity of 2000mg/l. That's 500 times higher than the strictest Canadian

standard. So do you deny the community this water? It's not up to you. The

community accepts this water. It's good water, because it's here, now.

Agreeable - the whole community must agree to co-operate in saving and contributing. If someone doesn't want to contribute do you deny them the water? Let's agree that there's a need that must be met. Let's agree to support ourselves and others. Everyone can agree with good water.

Exceptional - it's a fact of life that for the majority

of people in the world, clean water is the exception. UNICEF reports

that 64 % of the rural population (of Moçambique) do not have access

to safe water supplies while 75 % do not have access to sanitation facilities.

Exceptional - it's a fact of life that for the majority

of people in the world, clean water is the exception. UNICEF reports

that 64 % of the rural population (of Moçambique) do not have access

to safe water supplies while 75 % do not have access to sanitation facilities.

Precious

- like a jewel, like a treasure, clean water has to be kept under lock and

key.  The pumps are in the care of a committee which designates a specific

schedule of use, and at all other times the key is kept securely by the secretary

of the committee.

The pumps are in the care of a committee which designates a specific

schedule of use, and at all other times the key is kept securely by the secretary

of the committee.  Money meanwhile is often simply buried in the cow Krall.

Money meanwhile is often simply buried in the cow Krall.

Nothing is more precious than good water.

This is partly why the handover

of the pumps included a symbolic handover of a "treasure Chest" cashbox specifically

for the Pump committee to use for everything related to the pump.

Satisfying - PDARI employs facilitators and animators from the rural community to help the communities understand what is needed to obtain and maintain a pump. The satisfaction these young people get from seeing their communities achieve what was a seemingly impossible dream is only too evident. Such passion, pride, and satisfaction as a result of simple, good, water.

While it may seem absurd to ask a rural community earning less than a dollar

a day to show they can raise money to finance the operation and the

required spares, this is crucial to the sense of ownership needed. The actual

amount may seem meaningless: each involved family has to promise ten thousand

Moçambican meticais a month (1MT = $0.0000518) for a total of 52 cents a month. However, that's 4% of the entire

income for the month, which would be $96/month for average Canadians, a considerable

investment. I'd think twice about paying $96 a month for anything!

But having made that contribution, I'd make sure I got my moneys' worth.

So simple good water stimulates community involvement, future planning, and

a sense of ownership.

While it may seem absurd to ask a rural community earning less than a dollar

a day to show they can raise money to finance the operation and the

required spares, this is crucial to the sense of ownership needed. The actual

amount may seem meaningless: each involved family has to promise ten thousand

Moçambican meticais a month (1MT = $0.0000518) for a total of 52 cents a month. However, that's 4% of the entire

income for the month, which would be $96/month for average Canadians, a considerable

investment. I'd think twice about paying $96 a month for anything!

But having made that contribution, I'd make sure I got my moneys' worth.

So simple good water stimulates community involvement, future planning, and

a sense of ownership.

Of course it's not that simple. The PDARI (Programa de Desenvolvimento

de Água Rural de Inhambane (Inhambane Rural Water Development Program)

group spends many long hours working late into the Mozambican night to develop

the needed systems and plans, as well as ensuring communication with communities,

the local district and provincial governments, as well as the international

development donors (in this case CIDA is the principal donor).

Of course it's not that simple. The PDARI (Programa de Desenvolvimento

de Água Rural de Inhambane (Inhambane Rural Water Development Program)

group spends many long hours working late into the Mozambican night to develop

the needed systems and plans, as well as ensuring communication with communities,

the local district and provincial governments, as well as the international

development donors (in this case CIDA is the principal donor).

And this isn't

in some fancy office in a downtown tower! The PDARI office is in the

small town of Maxixe (pronounced ma-sheesh), some eight hours drive to the

north of the capital, Maputo (don't ask about the road!). They share

a very rundown office building with the local provincial water department,

and often find themselves working by emergency flashlight, or even candle

light! The power is mostly reliable, but when it gets dark it gets really

dark!

The project is led in country by Claudette Lavallee, through the Ottawa company Cowater International, with a local Moçambican team of six dedicated young people.

Logistics, Reliability, Maintainability

Familiar words to any engineer. But how do you set up a logistics chain to

provide a rural community, several hours walk from the nearest "formal" town,

spare parts in case of a breakdown. How do you trade off the need for the

pump to be reliable, against the need for it to be absolutely simple and

quick to repair if it should breakdown? How do you train a community to

maintain a device which as simple as it might be , is still bafflingly complex

to completely uneducated people?

Familiar words to any engineer. But how do you set up a logistics chain to

provide a rural community, several hours walk from the nearest "formal" town,

spare parts in case of a breakdown. How do you trade off the need for the

pump to be reliable, against the need for it to be absolutely simple and

quick to repair if it should breakdown? How do you train a community to

maintain a device which as simple as it might be , is still bafflingly complex

to completely uneducated people?

Most importantly, never underestimate people. Claudette explained she was amazed

by the capacity of volunteers from the community, who with no education

quickly grasped the concept and methods required. "Mechanical skills are

superb", she says. Concepts of scheduled maintenance, and preventive replacement

of parts were quickly grasped and firmly demonstrated. The project has been

running for a year's "probation" (or Guarantee period as Claudette likes

to call it) during which the community had to demonstrate the ability to

finance and maintain the pumps. So far every involved community has achieved

100% reliability!

Most importantly, never underestimate people. Claudette explained she was amazed

by the capacity of volunteers from the community, who with no education

quickly grasped the concept and methods required. "Mechanical skills are

superb", she says. Concepts of scheduled maintenance, and preventive replacement

of parts were quickly grasped and firmly demonstrated. The project has been

running for a year's "probation" (or Guarantee period as Claudette likes

to call it) during which the community had to demonstrate the ability to

finance and maintain the pumps. So far every involved community has achieved

100% reliability!

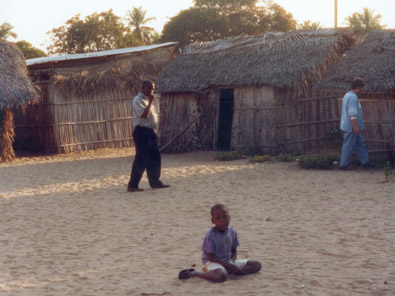

Inhamusua community attends the pump Opening

A typical Moçambican Rural Store.

Persuading local merchants to stock and re-order as necessary the required

spares has been a challenge. Quite frankly, the usual approach to spares

and stocks of anything is "wait till we run out then start looking for more".

Getting village shopkeepers to keep on hand something for which there may

never be a demand is "stimulating"! In the end a solid business case showing

how the shopkeepers can make a substantial profit is the only way to ensure

this is achieved. Development of entrepreneurial skills goes hand in hand

with "simple good water".

Opening the Pump

For this reason, the recent

official handover of the water pump infrastructure in the four rural communities

involved community people, village chiefs, district administrators, provincial

and national government representatives, donor representatives, and me as

an "ordinary Canadian" observer (it's our money too!)

In each community the message was the same: this is your pump, your responsibility. This was partly the reason why there was no identification on the pumps as

being "donated" by Canada. Each community is aware of their responsibility,

both for the pump to continue to supply the community, as well as the responsibility

to ensure the money involved is not wasted, their responsibility extends

beyond their community. (Although it's hard to imagine what the concept of beyond the community really

means : we were quite literally the first white people ever to visit some

of these communities. To explain how far Canada is to people with no conception

of the world beyond the local village centre, we resorted to saying you have

to drive for six weeks!)(and on these roads that's a long way)

This was partly the reason why there was no identification on the pumps as

being "donated" by Canada. Each community is aware of their responsibility,

both for the pump to continue to supply the community, as well as the responsibility

to ensure the money involved is not wasted, their responsibility extends

beyond their community. (Although it's hard to imagine what the concept of beyond the community really

means : we were quite literally the first white people ever to visit some

of these communities. To explain how far Canada is to people with no conception

of the world beyond the local village centre, we resorted to saying you have

to drive for six weeks!)(and on these roads that's a long way)

In each case the response was the same: thanks for giving people this opportunity

to prove they can succeed, great celebrations for the actual supply of water,

and a clear hope and expectation that life will truly improve.

In each case the response was the same: thanks for giving people this opportunity

to prove they can succeed, great celebrations for the actual supply of water,

and a clear hope and expectation that life will truly improve.

In line with reinforcing the message, in each village there was a formal signing of a contract by the village water committee. Paperwork, and writing still has an enormous element of importance in these communities, and the formality and gravity of the signing ceremony was impressive. Also impressive was that in three out of four communities, the responsible person signing the contract was a woman. Empowerment of women, and the role of women in African society is crucial to African Development.

In the end, the smiles on these peoples' faces says it all:

It's water: precious, simple, wonderful, water.

It's good water.

Back to Trips Index